College is widely agreed as a gateway

to income stability, general success, and job security. It makes sense that

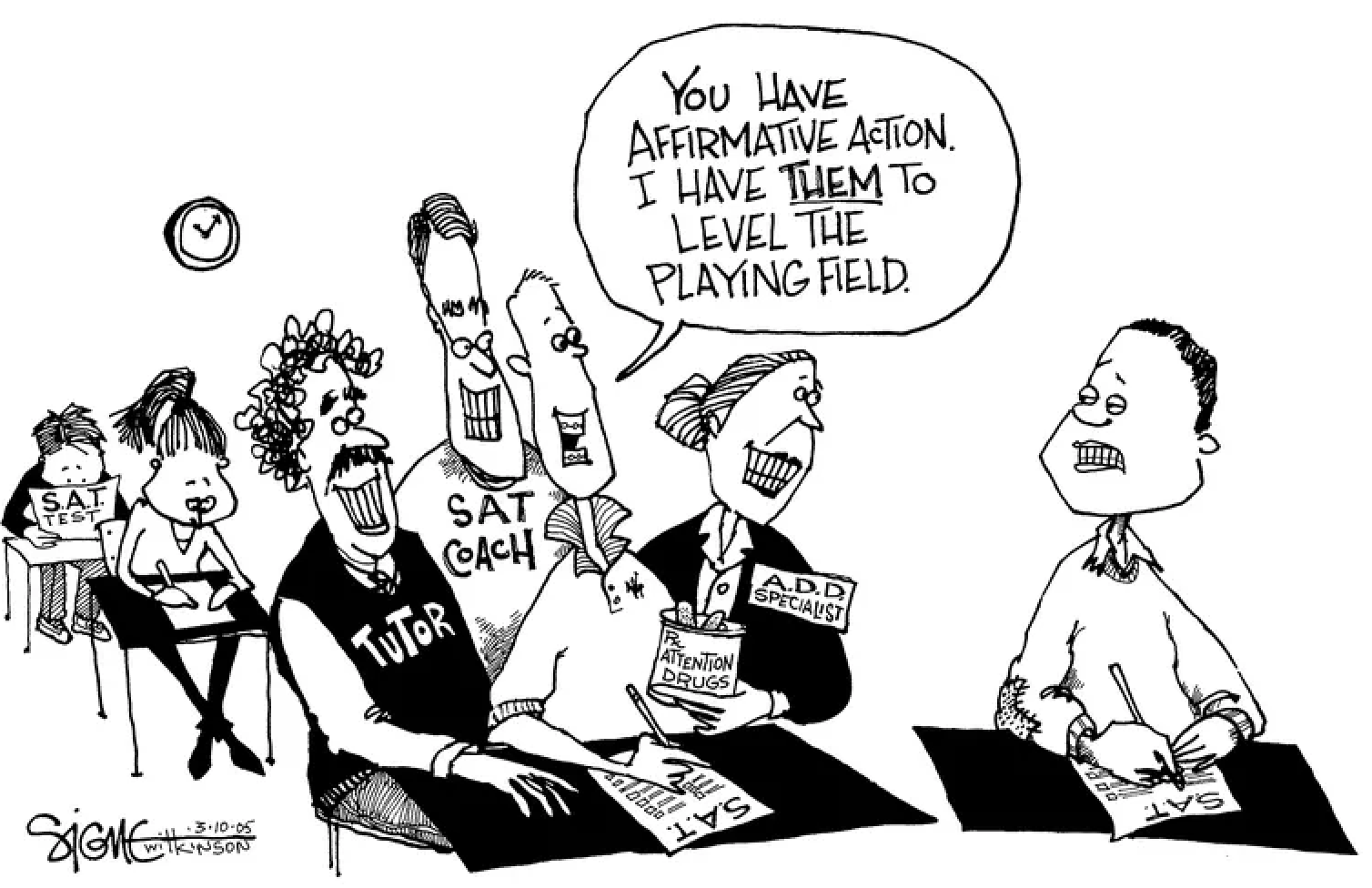

affirmative action is a highly debated topic. Hell hath no fury like a parent’s

scorn. When looking at college admissions and potential preferential treatment,

all parents, regardless of race, are invested in making sure their children

aren’t discriminated against during the process.

But what about the preference for

legacies in college admissions?

A legacy is someone who is related

to an institution’s alumnus. Therefore, colleges hold preferences for legacies,

citing reasons like upholding core university values and financial security. Being

a legacy means more than just having a leg up during admissions—a legacy’s

chances of acceptance can be two to four times more likely than those of a non-legacy

applicant. Often

labeled as the “white affirmative action” for rich, white, and well-connected

students, reports have stated that minority students only make up 6.7% of the

legacy applicant pools. 6.7 out of 100 percent. Generally, legacies make up 10 to 15 percent of the

annual freshman population at most elite institutions in the United States. At Georgetown

University, legacy applicants made over 30% of the entering class of 2021. Legacy programs are overwhelmingly

white and rooted in white supremacy. Being a legacy essentially requires a

lineage privileged enough to attend college. Black students were not admitted

into elite institutions for the vast majority of American history. Over its

400-year history, Harvard admitted a total of 12 Black applicants until the

1970s. Overt

forms of educational redlining, such as racial quotas or race-based exclusion rooted

in grandfather clauses, are cornerstones in every American elite institution.

In the 1920s, Harvard implemented a Jewish quota after noticing an ‘influx’ of

Jewish admits.

In the 1990s, Senator Dole

questioned the legitimacy of legacy admissions under the 1964 Civil Rights Act

for providing “unfair advantages” to students already born into wealth and

status. In

the early 2000s, Senators Lott and Edwards publicly admonished these programs

for upholding “special privileges” for white students and enforcing the

disproportionate negative impacts towards minority college applicants. With

this pattern of congressional criticism, are legacy programs legal?

Legacy programs are forms of off-brand

nepotism. Nepotism is unconstitutional under the Nobility Clause, which bans

officials from accepting titles from higher powers without congressional

permission. The only historial exception for collegiate legacy preference was strictly for military students during the 1800s. It made sense at the time—military

schools like West Point would hold preferences for applicants whose relatives died

in battle as those students were more likely to understand the heavy

implications of being in the army. Nonetheless, the definition of “war

veterans” eventually (predictably) shifted. Descendants of those in the upper echelons of the

military held more institutional value over those whose nameless fathers died

in battle. After public outrage alleging that institutions like West Point preferred

applicants belonging to the rich and powerful, Congress stepped in to re-narrow

the conditions of the legacy program. Preference would only be given to the descendants

of those who had fallen during service, partly as a means of reparations, and

would only be applied to a limited number of applicants—vastly decreasing the number

of legacy applicants. Presently, West Point no longer gives special considerations to

children of alumni.

This is not to say that legacy

applicants as individuals aren’t deserving of admittance to elite universities.

Most legacy students do comparatively well against their non-legacy

counterparts, and being a legacy doesn’t necessarily guarantee admittance. But

the issue isn’t how well legacy students do in school, it’s how they get there. If legacy

applicants were judged on the same playing field as others, 5 to 10% of legacy

students would not be admitted. Justice Powell, in his opinion for

Bakke (1978), asserted that universities hold the power to make their own

decisions in creating a diverse student body. But being a legacy doesn’t

increase student body diversity or prove an individual’s excellence; it’s just

a reflection of their family tree—one that is most likely rooted in privilege

and wealth. As Dannenberg states, an applicant’s ‘affinity’ for college should

be determined by how many obstacles they have overcome rather than the amount

of advantages in their life.

Legacy preference is meaningless

privilege. Colleges claim that those who have a history with their individual

institutions are more likely to have a “natural affinity” for the college

because they have inherited their parents’ drive and a stronger passion for a

university’s culture. However, drive is not inherited. The assumption that

legacies have more to offer an academic community solely because of their

parent’s alumnus status or because they know the campus football culture better

than other applicants, dismisses the potential contributions of students that come

from different or more disadvantaged backgrounds. As reflected in congressional

precedent and the Nobility Clauses, our nation’s predecessors decried

hereditary privileges as being antithetical to the American principle of

equality and democratic meritocracy. Even if 99% of a hypothetical entering class, whether

in colleges, Congress, or the military, is determined by non-hereditary

influences, upholding 1% of admittances based on generational connections is

still unethical.

Nevertheless, legacy admissions are

technically legal. In a case against the University of North Carolina, the

court judged that legacy programs were key to maintaining revenue to

universities and created a

non-binding precedent. However,

as recent critics have asserted, the legacy program is unconstitutional under

the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Public

universities that uphold legacy admissions violate the obscure provision that

denies “granting any Title of Nobility.” Furthermore, as legacy admissions

discriminate based on ancestry, it violates the 1866 Civil Rights Act. As

Kahlenberg states, the legality of legacy programs is a “myth.” White people have always had access to elite institutions. When colleges

claim preference for those with histories with higher education, they are

blatantly guarding the gilded side-door to continued white privilege.

Just

because it’s legal doesn’t mean it’s right. Legacy programs must be redetermined

under legal strict scrutiny and subsequently abolished.

By: Celeste Woojoo Roh